When a macaque has the choice between two lianasby Marie Delbasty and Julie Viana

Published by the May 10, 2021 on 8:00 AM

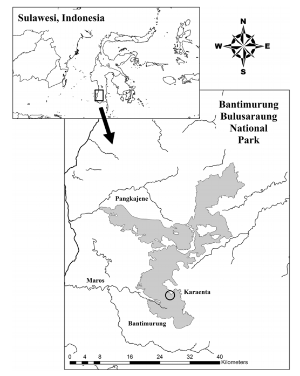

Two populations of moor macaques (Macaca maura) were studied in their natural environment in South Sulawesi, Indonesia in order to understand their use of two different habitats in karst forest.

Moor macaque is a species currently classified as "endangered" by the IUCN, mainly due to the disturbance and fragmentation of its habitat. That is why, in order to develop adequate conservation plans and management strategies, it is essential to study the patterns of habitat use in relation to the distribution of essential food resources.

Concerning the two types of habitat, they were characterized according to the vegetation present and its abundance as well as the topography and the presence of any trace of human activity.

The two habitats of this forest are in fact distinguished in two essential aspects:

The forest situated at the highest altitude with a steep slope, has few food resources but is not accessible to humans

vs.

The gently sloping forest, rich in resources but frequented by humans.

In order to carry out this study, each group of macaques was observed after having been accustomed to the presence of the scientists. The largest group consisted of about 30 individuals while the smallest group consisted of 18 macaques. The behaviour of the smallest group was studied from June to November 2016 while the largest group was studied from September 2014 to February 2015. Behavioural activities were defined as feeding, foraging, locomotion, social interactions and resting.

Although both habitats are used on a daily basis by each population, the analysis revealed that for both groups, the only behaviour that differed primarily between the two habitat types was time spent feeding. They spent more time feeding in the more food-rich forest habitat. The larger group spent more time overall in the food-rich forest while the smaller group spent more time in the food-poor forest.

The habitat with fewer resources is more of a refuge area for the macaques as they have no real predators and humans are the main threat. The larger group's use of a more productive but riskier habitat may be due to its history of provisioning, which may have allowed its individuals to have less fear of encountering humans. On the other hand, the individuals of the other group have never experienced provisioning. Another possible explanation is group size. Indeed, individuals in the larger group have less need to be vigilant because of their numbers, compared to the smaller group. In addition, the larger group might dominate the other group from a competitive point of view and thus be given priority for benefiting from resources.

In this context, macaques seem to be ecologically flexible, able to exploit the karst forest as a whole and to cope with human disturbance. It is important to protect the forest to allow the species to persist as habitat fragmentation threatens its survival. Thus, the management of this area would consist of balancing the needs of humans and macaques, and one of the solutions could be to educate local people on the protection of the species.

In a global context of loss of many species, the ideal would be to be able to leave in peace those for whom this is possible. Indeed, it seems preferable not to allow humans to access this area for the good of these macaques especially since this area is probably home to most of the remaining populations. Indeed, forest habitat with more food resources is a crucial part of the landscape for the survival of moor macaques in southern Sulawesi.

Thus, a question then arises:

would it be possible to let these macaques enjoy their habitats in peace while moving from one liana to another like Tarzan and Jane? To be continued…

Read the full study: Albani A., Cutini M., Germani L., Riley E. P., Oka Ngakan P. and Carosi M. (2020) Activity budget, home range, and habitat use of moor macaques (Macaca maura) in the karst forest of South Sulawesi, Indonesia. Primates 61, 673–684 (https://doi.org/10.1007/s10329-020-00811-8).

This post is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.Why should we think about cougars when planning our cities?by Amaïa Lamarins and Gautier Magné

Published by the February 3, 2020 on 2:02 PM

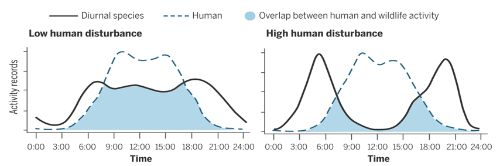

A puma family above the nighttime lights of San Jose - National Geographic - (photo courtesy of Chris Fust)Humans have modified 75% of earth land surface which has important consequences on wildlife. In fact, human presence and activities are perceived as a threat by animals which adapt their behaviors to avoid it. Gaynor and his collaborators’ meta-analysis showed that many species are modifying their daily activities and identified 117 diurnal mammals becoming more and more active at night. Consequently, these animals face constrained access to resources and are susceptible to shifting their diet to nocturnal prey. Thus, anthropic activities influence growth, breeding, survival and community interactions of wild animals.

Shift in rhythmic activity of diurnal species due to human disturbance - Ana Benítez-López.In southern California, the habitat of cougars, an apex nocturnal predator, is reduced by the expansion of cities. No, we’re not talking about the rampant nightclub predators (whose habitats remain undisturbed), we’re talking about mountain lions! You’ve probably already heard about pumas roaming across big cities like Santa Cruz, California. They likely are not curious tourists hoping to take in the sites, but are rather disturbed by human activities, which cause their nighttime activity to be higher in developed areas than in natural ones. This shift increases their daily energy expenditure: because of humans, pumas need to eat around 160-190 kg of additional meat per year (for females and males, respectively)! Are there sufficient deer populations to meet these needs? Unfortunately, it seems not, since a significant number of puma attacks on cattle have been recorded.

These results, showing human-induced behavioral change for pumas, come from a recent study published by members of the Santa Cruz puma project. By wide-scale monitoring of 22 wild pumas, they were able to link their behavior with their subsequent energetic expenditures: pumas’ behavior and movement were measured through spatial GPS location data, recorded every 15min, and energetic cost of movement was estimated considering their weight and travel velocity. An interesting methodological point to note: in order to avoid underestimating the energy expenditures via GPS tracking, scientists calibrated their estimations using accelerometers. Thanks to these methods they figured out the effect of housing densities on pumas’ activity and energetic costs, taking into consideration the time of day and sex of the animal.

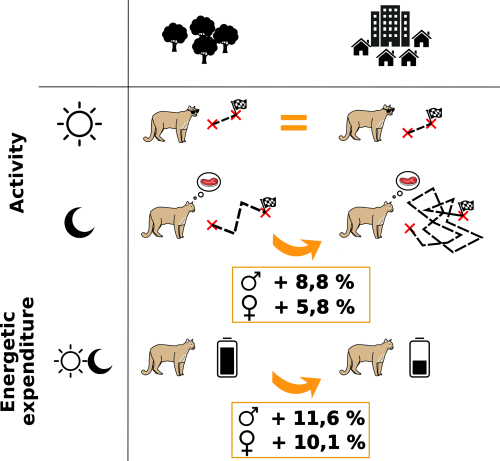

Indeed, they were right in taking into account these factors because, according to their findings, response to human activities differs between day and night and between males and females. During the day pumas are more likely to stay inactive, especially near urban areas. At night, being close to houses increases time spent active by 8.8% and 5.8%, respectively, for males and females. Consequently, estimated daily caloric expenditure increases by 11.6% for males and 10.1% for females in high housing density areas. Below you will find an outline summarizing these results:

Urban development negatively affects pumas by increasing nighttime activity and energy expenditure.Such studies underline the role of bioenergetics to estimate the costs of human-induced behavioral changes but do not provide insight on global energetic allocation. Further work is needed to understand the consequences of energetic balance disturbances and identify which individual functions are affected (growth, maintenance, maturation or reproduction). Besides, human impact could be underestimated because such tracking doesn’t allow us to know if pumas get all available energy from their prey near humans; some observations reported they often have to leave their prey because they fear humans. This partial feeding would constrain pumas to hunt more prey!

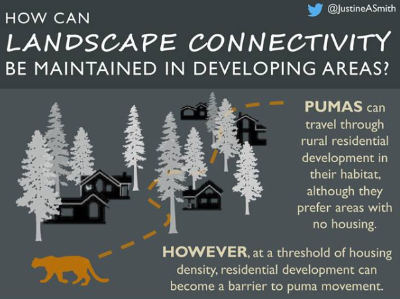

Unfortunately, this is not the only human-induced threat affecting pumas. In the region of Santa Cruz and southern California, they are targeted by ranchers, resulting in political tension about their conservation. In fact, cougars have been protected since 1990. However, 98 pumas are killed each year due to depredation hunting permits. It appears necessary to ensure coexistence between urban development, human activities, puma populations and their prey. In a recent study, development strategies are suggested, such as rural residence development, to ensure landscape connectivity and conservation of parcels where pumas have been geo-located. Nowadays, no cities are expanding regarding puma, deer or other wild animals’ living areas (to our modest knowledge!). The only measures taken when pumas are too close to urban zones consist in doing nothing or frightening or relocating it, and in the worst case killing it. And if designing our lives and activities regarding nature and wildlife was the challenge of tomorrow, would you be ready?

Ideal residential development maintaining pumas landscape connectivity. Graphical abstract of the paper of Smith and al 2019

This post is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.