Pyramids, built by the Egyptians and reversed by sharksby Pierre Labourgade, Valentin Santanbien and Morgan Schler

Published by the October 5, 2020 on 8:28 AM

The case of a extreme inverted trophic pyramid of reef sharks supported by spawning groupers in Fakarava, French Polynesia

Predators play a key role in the structure and functioning of ecosystems (Paine 1966; Begon et al. 2006). Through food webs, the relationship between preys and predators is crucial in order to maintain a balance, including in marine ecosystems (Woodson et al. 2018). A trophic pyramid is a graphic representation designed to show the biomass at each level of the food chain. The lowest level starts with decomposers and the pyramid ends with top predators. This is called a pyramid because generally, the biomass in the lower levels turns out to be much higher than in the upper levels (Figure 1 A). However, in the marine environment, and in some remote and almost unoccupied areas, predators may dominate in terms of biomass, generating an inverted pyramid (Figure 1 B).

Figure 1 Diagram of a normal (A) and inverted (B) trophic pyramidAggregations of grey reef sharks, Carcharhinus amblyrhynchos are observed on some reefs in the Indo-Pacific (Robbins 2006) (Figure 2). The southern pass of Fakarava atoll in French Polynesia has a population of around 600 individuals of this species (Mourier et al. 2016) (Figure 3). This makes it one of the few places to present such a large grouping. With such a large population on a reef channel of just over 1 kilometer, the area has up to three times the biomass per hectare documented for any other reef shark aggregation (Nadon et al. 2012). The biomass of predators is then much greater than preys, thus generating an inverted trophic pyramid. During this study, scientists tried to understand how those large group of sharks can survive when prey biomass is insufficient.

Figure 2. Aggregation of grey reef sharks

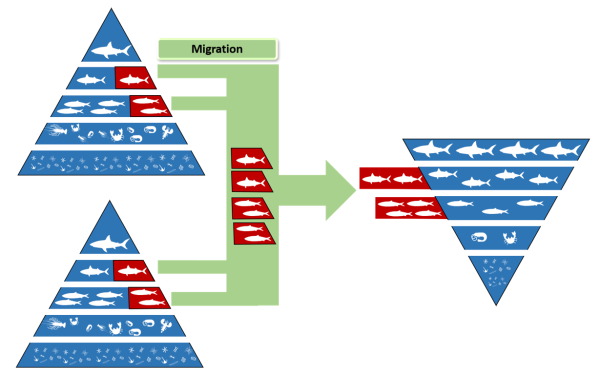

Figure 3. Panoramic view of Fakarava atollDuring the study period, video-assisted underwater visual surveys conducted across the pass allow the researchers to find that sharks population can represent up to 700 individuals. Then, scientists use bioenergetic models based on known value of parameters that influence energetics needs of shark-like “asymptotic length”, “growth rate” or “proportion of fish in the diet” to determine prey biomass needed for all the individuals. According to bioenergetic models, the food requirements to maintain that large population is approximately 90 tons of fish per year, which is not provided by the environment as it is. However, the pass is used as a breeding ground for many fish species, thereby reducing the prey-shark ratio. This means that the prey biomass will be much higher than that of sharks during these reproduction periods (Mourier et al. 2016), leading to frenetic predation behavior in the shark that will allow it to meet its energy needs (Robbins and Renaud 2016; Weideli, Mourier, and Planes 2015). Furthermore, the continuous presence of prey aggregation is ensured by the successive migration of different species to this site, in order to meet the metabolic demands of the shark population present (Craig 1998). With simulation-based on researcher bioenergetic model, sharks would not have enough energetic income after 75 days if other prey species didn’t migrate to the pass. There is, therefore, an idea of metapopulation where the exchange of individuals between populations in normal and inverted trophic pyramids ensures that the energy needs of each individual are met (Figure 4). This exchange of individuals between populations will allow the long-term maintenance of the species and, in the case presented here, of the shark.

Figure 3. Diagram of the transfer of potential prey for the shark between two normal pyramids and one inverted trophic pyramid via migratory flowsThe temporal aspect in the movement of individuals between populations is therefore important to be considered during the development of management and conservation measures. Indeed, if we want to ensure the sustainability of the grey reef shark in this pass, we must not only protect the habitat on-site, but also the original habitat of different species that come to reproduce in the pass. These species are indeed essential for the survival of sharks since they represent the only source of energy available during certain periods of the year.

Other cited articles:

This post is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.A new way to understand the effects of toxic compoundsby Flore Emonnot and Anne Michaud

Published by the September 7, 2020 on 8:07 AM

Water pollution is a major concern. It can be induced by many elements. For example, Cadmium (Cd) which belongs to the heavy metals family can be source of pollution in certain concentrations. This element is naturally present in the environment, but the use of agricultural chemicals has been indicated as the main anthropogenic source of Cd pollution in aquatic environments. The organisms living in these aquatic ecosystems are exposed to this pollution. Moreover, this compound is bioaccumulated in organs and tissues, so it can induce damages.

Daphnia magnaThat is why it is important to evaluate the effects of this pollutant on organisms. Daphnia magna (a cladoceran crustacean) is one of the most widely used animals in aquatic toxicology. In terms of sensitivity to toxic substances, it is generally thought to be representative of other zooplankters (Anderson, 1944). It plays an important role in the balance of an ecosystem, because of its position on the first levels of the food chain. Also, D. magna enhances water purification by filtering water and retaining food particles, it is its way to eat. This animal spends its whole life in a variety of freshwater environments. As long as the conditions remain favourable, it reproduces predominantly by parthenogenesis.

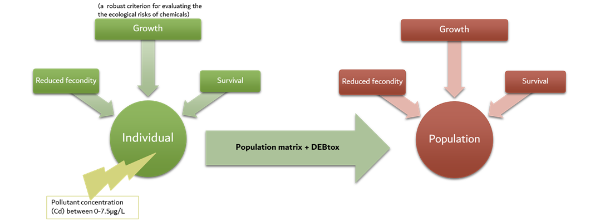

Bioassays are used in aquatic toxicology to provide individual-level information, while ecotoxicology is assessing the impact of pollution on populations. The DEB theory (Dynamic Energy Budget) is a theory that describes the aspects of metabolism (energy and mass budgets) at the individual level. Food assimilation results in energy, which can then be used for reproduction, growth or maintenance (life-history traits). The DEBtox is a toxicological application of the DEB theory which attempts to assess the effects of pollutants on life-history traits over time.

The key challenge is how to infer the impact of toxic effects observed in individuals and apply it to an entire population. Elise Billoir and her team combined the following tools to extrapolate the individual effects to the entire population:

The DEBtox is a good way of modeling survival, reproduction and growth continuously as a function of time and exposure concentration and at the individual level.

The population growth rate (which incorporates lethal and sublethal effects), is the best parameter to evaluate the risk of a pollutant on a population, hence matrix population models are a useful tool. Billoir explains that in population matrix, population is divided into classes based on development stage, and individuals transfer from a class to the next one depending on their survival and their fecundity.

By combining DEBtox theory and matrix population models, it is possible to extrapolate every effect of the toxic compound on the individual to the population level (as explained in the synthetic diagram below).

This technique used by Billoir, has not yet been used in an ecotoxicological context. It consists of reorganizing all the age-specific information in a stage-specific way. This way it makes possible to compare the sensitivity in the face of cadmium and in relation to the age of the individual.

Diagram of the method developed in the study of Billoir et al.In this case, the sensitivity analyses showed that the effects of cadmium at the individual level were not significant but the application of the model proved that the population growth rate is highly affected through the cadmium contamination. Moreover, we think that this model could be applied to similar aquatic organisms and other pollutants such as heavy metals and could be useful to enhance existing bio-indicators of water quality.

This post is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.Spatial response of plaice and sole to climate changeby Arnaud Dupond and Alix Pascal

Published by the August 3, 2020 on 7:54 AM

Scientists admit that climate change is one of the main driving forces which change species distribution and abundance in many ecosystems.

In this case, a modification of abiotic variables can affect the “niche concept” and can also change species geographical distributions. For the marine environment, this notion of geographical dependence is important. Indeed, marine organisms show several distinct stages during their life and each of these stages evolve in a specific habitat.

The objective of this study was to use different models based on physiological aspects and environmental variables in order to estimate habitat occupation by plaice and sole under different climate change scenarios in the North Sea.

How to reach this objective?

To predict new habitats, researchers considered environmental variables and determined their effect on the food web, but also the effect of the food web on the water chemistry. To do that, the ecosystem model used functional groups of taxa. Their taxa are phytoplanktonic, planktonic and macrobenthic organisms. Some of them have a direct effect on the water chemistry and are regulated by other taxa. The food web is also used to quantify the availability of the habitat’s resources. Thanks, of this two types of model results fit more precisely reality of the distribution.

The sample strategy is built like this, data are collected daily on surface of 10x10km sin the North Sea.

Figure 1: Schematic simplification of the models used in the studiesResults of the study

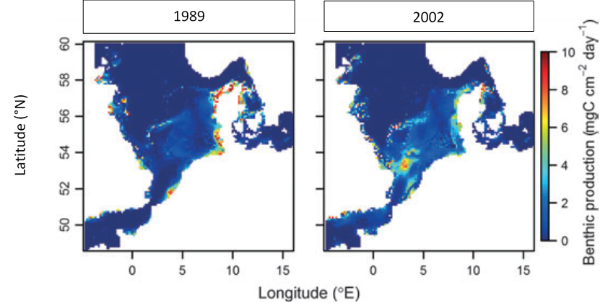

The model of environmental variables shows the predictions for temperature and food conditions between 1989 and 2002. This data showed benthic production is concentrated along the southern coast during the year 1989, whereas in 2002 is concentrated in the Southern bight (figure 2).

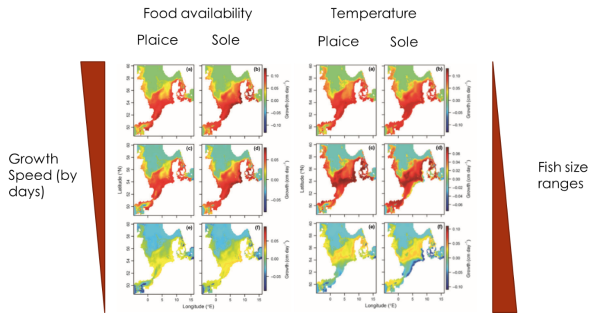

Figure 2: Comparison of the benthic production between 1989 and 2002 in the North SeaAn important fact is that the temperature rate inside of which the growth is positive will change with the size of the fish and according to abundance of food (the more food is abundant the higher rate of temperature is). Indeed, bigger fish need higher temperature to grow optimally. Figure 3 defines the areas of maximum potential daily growth of each class size of plaices in 1989 at the left, and in 2002 at the right.

Figure 3: Comparison between the three size ranges of plaices and soles, of the speed growth in regard of two environmental parameters, the food availability and the temperatureThe results for maximum potential growth per day seem to give the same result as the estimate of average abundance. (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Comparison of the plaice and sole abundance distribution in the North SeaConclusion

For the plaice, migrations during different stages of life maximize their physiological performance during the summer season, in the winter, the adult’s distribution is determined by the best spawning habitat and shows maximisation of their fitness. Sole differs in their physiological traits and have a higher optimal growth temperature which explains the difference in life habitat. As for plaice, the area indicated high quality habitat for the different size class.

This study can predict the evolution of species distribution with a model of environmental changes and one of physiological changes but in our case, we can just explain data collected not the prediction made with the model.

Read the full study: Teal, L.R., van Hal, R., van Kooten, T., Ruardij, P. and Rijnsdorp, A.D. (2012), Bio‐energetics underpins the spatial response of North Sea plaice (Pleuronectes platessa L.) and sole (Solea solea L.) to climate change. Glob Change Biol, 18, 3291-3305. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2012.02795.x

This post is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.Microplastics: no effect on the productivity of the marine environment?!by Amaelle Bisch and Anaelle Bouloy

Published by the July 6, 2020 on 2:45 PM

According to the paper: “Do microplastics affect marine ecosystem productivity?” by Troost et al. 2018, microplastics would have almost no effect on primary and secondary production, or at least this effect could not be demonstrated!

But what are microplastics?

But what are microplastics?Plastics appeared at the beginning of the 20th century and quickly became indispensable in everyday life. Plastics are composed of polymers (long carbon chain) of synthetic or natural origin. Microplastics are plastic particles smaller than 5 mm (. There are two types of microplastics: primary (directly manufactured at this size) and secondary (resulting from the degradation of macroplastics). The major disadvantage of microplastics is that they are easily ingested by marine biota (2,3).

Primary production, the basic link in a long chain

Primary producers are at the base of the trophic chain. They are autotrophic organisms that produce their organic matter from a light (photosynthesis) or mineral source. In the marine environment, these organisms correspond to algae, phytoplankton and cyanobacteria and are the basis for zooplankton feeding. Zooplankton are secondary producers and heterotrophic organisms unable to synthesize their organic matter.

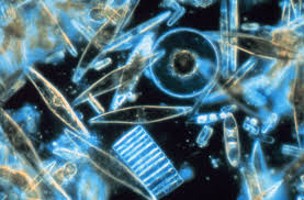

Phytoplankton

ZooplanktonHow can microplastics affect these organisms?

In most of laboratory experiments, the impacts showed on plankton, they were for primary producers an inhibition on the algae growth, chlorophyll content and photosynthesis (4,5,6). For zooplankton, it was observed a reduced food consumption and an increasing in energy consumption with a low allocation of this energy for growth (7,8). But these effects depend to the species of plankton and the nature of microplastics (9). However, are these observations noted in the laboratory really transposable to the ecosystem scale?

The models spoke...

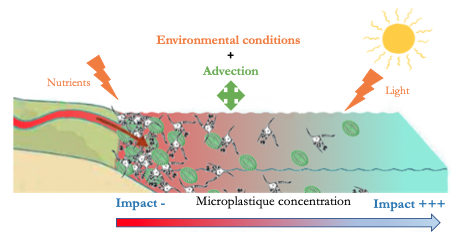

The study by Troost et al. (1) shows, by means of modelling, that at the level of primary production (algal biomass) there is no significant impact of microplastics. Indeed, this can be explained by different theories: (i) environmental conditions (availability of nutrients and light) already strongly impact the growth of algae, (ii) a transport technique (advection) would provide some protection.

Concerning zooplankton, or secondary production, the impact of microplastics is considered low over the entire North Sea because the observed changes are both positive and negative and therefore compensate each other. Exposure to microplastics leads to changes in spatial patterns and strangely enough the impact is not greatest in areas with the highest concentration of microplastics. Surprising but not so much because this can be explained simply by the small concentrations of algae found in off-shore areas (areas with the least concentration of microplastics) making zooplankton more sensitive to any change.

And how they have managed to demonstrate that?

The difficulty lies in a successfully integration of the data observed in the laboratory into an ecosystem-scale model. They modelled biogeochemical transport, hydrodynamics, nutrient inputs from rivers, primary production, zooplankton biomass and also microplastic concentrations in the North Sea. In the end, the results obtained are only based on modelling and could not be verified in the field, so the conclusions should be "swallowed" with caution.

Cited articles

- Troost, A., Desclaux T., Leslie, A., Van Der Meulen, M., Dick Vethaak, A., 2018. Do microplastics affect marine ecosystem productivity? Marine Pollution Bulletin 135 (2018) 17–29

- Ivar do Sul, J., Costa, M.F., 2014. The present and future of microplastic pollution in the marine environment. Environ. Pollut. 185, 352–364. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j. envpol.2013.10.036.

- GESAMP, 2016. Sources, fate and effects of microplastics in the marine environment: part two of a global assessment. In: Kershaw, P.J., Rochmann, C.M. (Eds.), IMO/FAO/ UNESCO-IOC/UNIDO/WMO/IAEA/UN/ UNEP/UNDP Joint Group of Experts on the Scientific Aspects of Marine Environmental Protection. Rep. Stud. 2016pp. 220 GESAMP No. 93.

- Zhang, C., et al., 2017. Toxic effects of microplastic on marine microalgae Skeletonema costatum: interactions between microplastic and algae. Environ. Pollut. 220, 1282–1288.

- Sjollema, S.B., et al., 2016. Do plastic particles affect microalgal photosynthesis and growth? Aquat. Toxicol. 170, 259–261.

- Casado, M.P., et al., 2013. Ecotoxicological assessment of silica and polystyrene nano-particles assessed by a multitrophic test battery. Environ. Int. 51, 97–105.

- Watts, A.J., et al., 2015. Ingestion of plastic microfibers by the crab carcinus maenas and its effect on food consumption and energy balance. Environ. Sci. Technol. 49, 14597–14604.

- Van Cauwenberghe, L., et al., 2015. Microplastics are taken up by mussels (Mytilus edulis) and lugworms (Arenicola marina) living in natural habitats. Environ. Pollut. 199, 10–17.

- Wenfeng Wang, Hui Gao, Shuaichen Jin, Ruijing Li, Guangshui Na, 2019. The ecotoxicological effects of microplastics on aquatic food web, from primary producer to human: A review. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 173, 110–117

This post is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.A little bit of salt and heat... a good recipe for goby metabolism?by Maxime Deau, Quentin Garreau and Dorian Raoux

Published by the June 1, 2020 on 2:18 PM

As the literature shows, a variety of factors influence the well-being of fish populations. For example, we know that some fish may or may not be very sensitive to changes in the conditions of their living environment (water temperature or salinity). These changes can affect their metabolism (reduced fertility, growth, etc.) or even, in the worst case, lead to the death of individuals. The goby (Pomatoschistusmicrops) (Figure 1), a relatively tolerant species and an essential central link in the food web is one of the species studied in the observation of the impact of these changes on the fish fauna in the Minho estuary in Portugal (Figure 2).

In this study, the researchers were able to model the evolutionary dynamics of p.microps populations based on models that take into account different parameters of goby's life cycle like fertility, mortality, migration rate and the effect of environmental parameters such as salinity and temperature. The aim of these models is to describe the evolution of the different life stages of this fish by establishing the possible impacts of climate change on their metabolism. In this framework, they studied both the impacts of temperature and salinity and combined the impact of both.

It has been noted that salinity directly influences the metabolism of individuals. Indeed, it plays a particular role in the survival of many aquatic organisms but also on their growth (strong allocation of energy to osmoregulation; Rigal, F. and al.,2008). Therefore, it plays a role in the growth of the goby as well as indirectly on its prey. The latter will be less available, which implies a higher energy expenditure for predation. However, this species resists large variations in salinity (0 to 51 psu). For temperatures, the impact is more diverse. Since the goby does not thermoregulate, its metabolism is directly influenced by the temperature of the environment. In addition to its significant effect on pregnancy, it also has an impact on migration, reproduction, recruitment and mortality. (Sogard, 1997; Hurst et al., 2000; Hales and Able,2001; Hurst, 2007; Jones and Miller, 1966; Claridge et al.,1985; Wiederholm, 1987).

Regarding the goby’s responses to these parameters, the research team has implemented them in the model, running different scenarios (salinity and temperature variations). Temperature and salinity variations studied separately led to population crash, except for a salinity lower than the current state ( -5psu). However, the combination of the two variables gave scenarios showing an increase in the population when the salinity was -5 psu, with temperatures ranging from +1 to +3°C, with an optimum at +2°C (see figure 5).

For example, in extreme temperatures, the fish activity will be greatly reduced, which will imply a decrease in the search for preys or sexual partners, causing feeding and mating problems (predation of eggs by males (Magnhagen, 1992). However, a slight increase in temperature could cause a longer reproduction period, allowing for a greater number of offspring to be generated. It has also been noted that with an increase in temperature, there is a delay in the breeding period, leading to the appearance of offspring in a period that may be less favorable for their proper development (early winter/lower metabolism).In conclusion, climate change, through its effects on water temperature and salinity, will have a significant impact on common goby populations. Indeed, these parameters have a great influence on the metabolism of these fish (whatever their stage of development).In many scenarios, increases in temperature and salinity can cause crash populations. But beware, in some cases (increase in temperature and decrease in salinity) the population of Pomatoschistus microps would tend to increase. Even if this scenario seems favorable for this species, some others will suffer. in fact, a study conducted on Arctic fish species has confirmed these trends

It is therefore clear that climate change affects population dynamics by changing fish environment and impacting their metabolism. It’s therefore important to continue this kind of study to have a better idea of these repercussion on a global scale. We are largely responsible for climate change, so it is up to us to make sure that we limit our impacts. Here is a link that will teach you how to reduce your carbon footprint through 20 examples of simple everyday actions: http://www.globalstewards.org/reduce-carbon-footprint.htm

Other cited studies:

Claridge, P.N., Hardisty,M.W., Potter, I.C., Williams, C.V., 1985. Abundance, life history and ligulosis in the Gobies (Teleostei) of the inner Severn Estuary. J.Mar. Biol. Assoc. U. K. 65, 951–968.

Hales, L.S., Able, K.W., 2001.Winter mortality, growth, and behavior of young-of-the-year of four coastal fishes in New Jersey (USA) waters. Mar. Biol. 139, 45–54.

Hurst, T., 2007. Causes and consequences of winter mortality in fishes. J. Fish Biol. 71, 315–345.

Hurst, T.P., Schultz, E.T., Conover, D.O., 2000. Seasonal energy dynamics of young of the year Hudson River striped bass. Trans. Am. Fish. Soc. Taylor & Francis 129, 145–157.

Jones, D., Miller, P.J., 1966. Seasonal migrations of the common Goby, Pomatoschistus microps (Kroyer), in Morecambe Bay and elsewhere. Hydrobiologia 27, 515–528.

Magnhagen, C., 1992. Alternative reproductive behaviour in the common goby, Pomatoschistus microps: an ontogenetic gradient? Anim. Behav. 44, 182–184.

Rigal, F., Chevalier, T., Lorin-Nebel, C., Charmantier, G., Tomasini, J.-A., Aujoulat, F., Berrebi, P., 2008. Osmoregulation as a potential factor for the differential distribution of two cryptic gobiid species, Pomatoschistus microps and P. marmoratus in French Mediterranean lagoons. Sci. Mar. 72, 469–476.

Sogard, S.M., 1997. Size-selective mortality in the juvenile stage of teleost fishes: a review. Bull. Mar. Sci. 60, 1129–1157.

Wiederholm, A.-M., 1987. Distribution of Pomatoschistus minutus and P. microps (Gobiidae, Pisces) in the Bothnian Sea: importance of salinity and temperature.Memoranda Societatis pro fauna et flora Fennica 63, 56–62.

This post is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

How to adapt your birdly behavior to the river flow?by Mireia Kohler Pacino and Oihana Olhasque

Published by the May 4, 2020 on 2:05 PM

The natural flow regime paradigm and the aim of study

In 1997, the natural flow regime paradigm has been established. This paradigm has become a real basement of management and basic biological study of running water ecosystems (Poff et al., 1997). This one establishes that the temporal variation in river flows requires the adaptation of structure and function of the aquatic ecosystems. To better understand this adaptation, many animals have been studied. In our case, the Cinclus Cinclus is chosen because of his large distribution in the world. We want to figure out if his behavior and energy use strategies are dictated by the natural river flow. We’ll use time-activity and time–energy budgets. In fact, it has proved to be a convenient approach to assess a bird's use of time and energy expenditure.

Using time-activity budget

Different behaviors of dippersTo answer to this question, the time-activity budget of the White-throated Dipper (Cinclus cinclus) was studied within a water basin in the Pyrenees, where natural flow regime is highly seasonal. To study the time activity budget, bird activities were categorized under four main headings: resting, foraging, diving and flying. In the study, between October 1998 and August 2001, birds activities were monitored each month using a portable tape recorder in combination with a telescope at a distance of 30–100 m. Overall, the analysis was made on 130 recordings: 62 males, 52 females, and 16 birds of unknown sex. As strategies could depend on external and river conditions, air temperature, water temperature and water column depth were measured on the behavioral surveys.

Parameters used in the study

Authors assumed that the Daily Energy Expenditure is calculated from an equation that includes time-energy budgets (obtained by incorporating time activity data), basal rate of metabolism, thermoregulation, locomotion, foraging, digestion, growth, reproduction, as well as all energy expenditures that eventually end up as heat production. The required foraging rate and the observed rate of energy gain were also calculated by dividing Daily Energy Expenditure with, respectively, the active day length for birds and the total time spent feeding by birds. Consequently, the ratio “Observed rate of energy gain” / “Required foraging rate” indicates how much faster observed feeding rates are in relation to minimum required feeding rates. For example, if birds gather food at a rate just enough to balance their energy budget then this ratio is equal to 1.

Parameters used in the DEE equationResults synthesis

The natural river flow is high during snowmelt (between April and June) and very low in summer. The behaviors are also chasing due to season: In winter our birds spend more time in foraging where food is rarely found and the water flow didn’t increase. In May, went the river flow increase, they have a rest for 70% of the day. Diving, flying and other activities showed no peculiar pattern, but there’s a relationship between water stage and time spent diving. Moreover, the ratios, observed rate of energy gain / required foraging rate indicated our birds could face high energy stress during winter but paradoxically none during high snowmelt spates when food is expected to be difficult to obtain. Unfortunately, the daily energy expenditure doesn’t seem to show any annual pattern. At this step of the study, they couldn’t find out whether Dippers use an energy strategy.

To go further....

With the actuals methods like calorimetry will be a complement to this study. To figure out, more information about dippers cycle life and potentials energy strategies. More generally, this study will serve the overwhelming challenge of maintaining native birds (especially those at risk) and more generally speaking biodiversity in human-altered rivers and streams.

This post is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.Shad, those endangered travelersby Alicia Dragotta and Claire Valleteau

Published by the April 6, 2020 on 1:52 PM

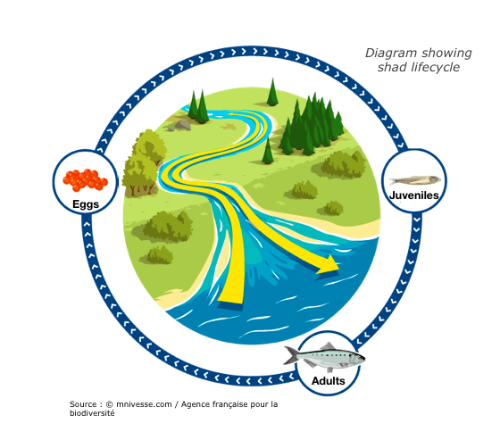

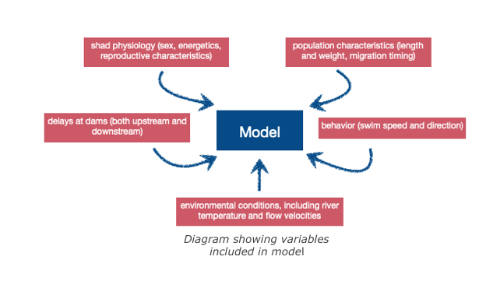

Photograph by MRM associationShad are migratory fish that travel great distances between sea and river in order to reproduce. These long journeys are the source of great energy expenditure, particularly to find the most favourable spawn environment. These species are considered bio-indicators of our waterways. Their presence or absence indicates the ecological state of the water. Migratory distance was governed by energetics, behaviors, maturation, and upstream delays at dams. Individual adult migrant American shad (Alosa sapidissima) ascend the Connecticut River and spawn, and survivors return to the marine environment. Theodore Castro-Santos and Benjamin H. Letcher presented a simulation model of these behaviors.

The purpose of this model is to evaluate the effects of biological and physical variables on adult spawning success and survival. Only energy devoted to migration has been taken into account in the model. Physiology and energetics strongly affected distribution of spawning efforts and survival into the marine environment. Delays to both upstream and downstream movements had dramatic effects on spawning success. Other factors influencing migratory distance included entry date, body length, and initial energy content. Furthermore, dams alter reproductive success and have an impact on migration (delay).

This model suggests shad that spend more time in the river have greater spawning success but are more likely to die of energy depletion. Many important factors in the models presented here remain enigmatic. Perhaps the most important question is what causes shad to reverse direction and migrate downstream. Do both energetics and maturation play a role ?

Answering this question could be difficult but may be possible using, say, a combination of physiological telemetry (e.g., Hinch et al. 1996) and data on reproductive status, especially of downstream migrants. The purpose of this paper was to develop a management tool to evaluate the relative importance of biological and physical factors on shad reproduction and survival. Restoring access to spawning habitat by providing fish passage has been a central management strategy. Ecological continuum is very important to preserve species, including these migratory fish. Dams for example, were built for many reasons, at the origins in order to mill operations, and today for hydraulic energy exploitation. We have to reconsider the interest of these dams, remove those which are useless and adapt the others. This process has been under way for several years, opening the door to restoring access to the rivers.

Read the full study: Castro-Santos, T. and Letcher, B.H. (2010) Modeling migratory energetics of Connecticut River American shad (Alosa sapidissima): implications for the conservation of an iteroparous anadromous fish. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences. 67(5): 806-830. https://doi.org/10.1139/F10-026

This post is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.Corals and algae, a relationship in danger: a model to predict their future! by Clara Dignan, Anna Gago and Anabelle Leblond

Published by the March 2, 2020 on 2:14 PM

Bleached branching coral (foreground) and normal branching coral (background). Keppel Islands, Great Barrier ReefCorals that come together to form coral reefs are shelter to 25% of our planet's marine life according to the WWF. This biodiversity is fundamental. It’s both a source of income and food, and it provides irreplaceable services to humanity. But today coral reefs are in danger. They are directly threatened by global warming. In forty years, 40% of the reefs have already disappeared and scientists agree that if nothing is done by 2050, all of them will be gone (Coral guardian).

Coral polyps and algae, an endosymbiotic relationship

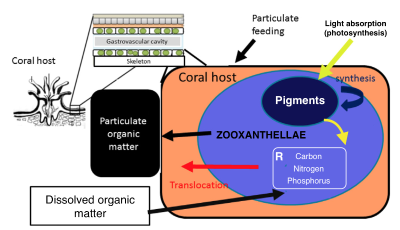

Coral bleaching has now become a major global concern for the future of coral reefs. Temperature rise appears to be one of the main causes of bleaching, affecting growth, feeding and other ecological processes on reefs. This bleaching phenomenon is due to the expulsion of zooxanthellae, the symbiotic microalgae living in the tissues of the polyps (the coral is made up of a colony of polyps that participate in the making of its skeleton). These unicellular algae carry out photosynthesis and provide, for the most part, the energy that corals need to develop and grow. Exchanges between the polyp and the zooxanthellae mainly concern nitrogen, phosphorus, carbon and biosynthetic intermediates. The presence of zooxanthellae being responsible for the color of the colonies, bleaching is therefore the symptom of a coral which is no longer in symbiosis, which generally results in the death of the coral.

The coral-symbiont relationship and its interaction with the overlying water column.Prediction models

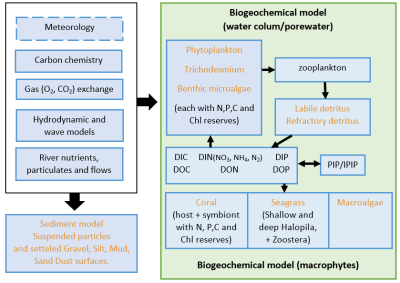

Since few year, scientists analyze corals and try to predict their bleaching evolution. In this aim, a collaboration between several organizations such as CSIRO have set up a first hydrodynamic, sedimentary and biogeochemical model called: « eReef ». This model simulates the environmental conditions as the temperature, the background light and the organic nutrient concentration of the Great Barrier Reef at several scales. It allows accurate prediction of factors influencing coral processes from satellite remote sensing images.

However, for more representative modelling, it is necessary to apply models that take into account the coral-symbiont relationship and the stress related to environmental variations. In this framework, Baird et al. have developed a model which, in parallel to the environmental conditions obtained from the « eReef » model, also takes into account essential parameters in the symbiotic process such as biomass and growth rate of zooxanthellae, pigment concentration, nutritional status as well as tolerance characteristics such as sensitivity to reactive oxygen concentration (oxidative stress).

The eReefs coupled hydrodynamic, sediment, optical, biogeochemical model. Orange labels represent components that either scatter or absorb light levels. (For a better understanding of the colour used and the abbreviations, the reader is referred to the web version of the article)Take home message

This coral bleaching model applied under realistic environmental conditions has the potential to generate more detailed predictions than satellite coral bleaching measurements. In addition to predicting coral bleaching, this model will now make it possible to evaluate management strategies, such as the introduction of temperature-tolerant individuals or species or localized shading.

Nevertheless, this model is still too simplistic to make real predictions. It is based only on the process of a single type of coral and macro-algae and does not take into account all phenomena related to bleaching. It is therefore seen as a step forward for science that could allow for future reevaluations of the effects of bleaching.

Bibliography

Why should we think about cougars when planning our cities?by Amaïa Lamarins and Gautier Magné

Published by the February 3, 2020 on 2:02 PM

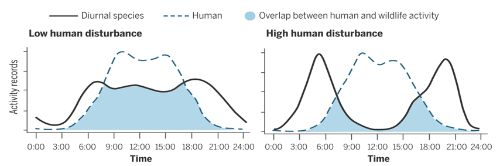

A puma family above the nighttime lights of San Jose - National Geographic - (photo courtesy of Chris Fust)Humans have modified 75% of earth land surface which has important consequences on wildlife. In fact, human presence and activities are perceived as a threat by animals which adapt their behaviors to avoid it. Gaynor and his collaborators’ meta-analysis showed that many species are modifying their daily activities and identified 117 diurnal mammals becoming more and more active at night. Consequently, these animals face constrained access to resources and are susceptible to shifting their diet to nocturnal prey. Thus, anthropic activities influence growth, breeding, survival and community interactions of wild animals.

Shift in rhythmic activity of diurnal species due to human disturbance - Ana Benítez-López.In southern California, the habitat of cougars, an apex nocturnal predator, is reduced by the expansion of cities. No, we’re not talking about the rampant nightclub predators (whose habitats remain undisturbed), we’re talking about mountain lions! You’ve probably already heard about pumas roaming across big cities like Santa Cruz, California. They likely are not curious tourists hoping to take in the sites, but are rather disturbed by human activities, which cause their nighttime activity to be higher in developed areas than in natural ones. This shift increases their daily energy expenditure: because of humans, pumas need to eat around 160-190 kg of additional meat per year (for females and males, respectively)! Are there sufficient deer populations to meet these needs? Unfortunately, it seems not, since a significant number of puma attacks on cattle have been recorded.

These results, showing human-induced behavioral change for pumas, come from a recent study published by members of the Santa Cruz puma project. By wide-scale monitoring of 22 wild pumas, they were able to link their behavior with their subsequent energetic expenditures: pumas’ behavior and movement were measured through spatial GPS location data, recorded every 15min, and energetic cost of movement was estimated considering their weight and travel velocity. An interesting methodological point to note: in order to avoid underestimating the energy expenditures via GPS tracking, scientists calibrated their estimations using accelerometers. Thanks to these methods they figured out the effect of housing densities on pumas’ activity and energetic costs, taking into consideration the time of day and sex of the animal.

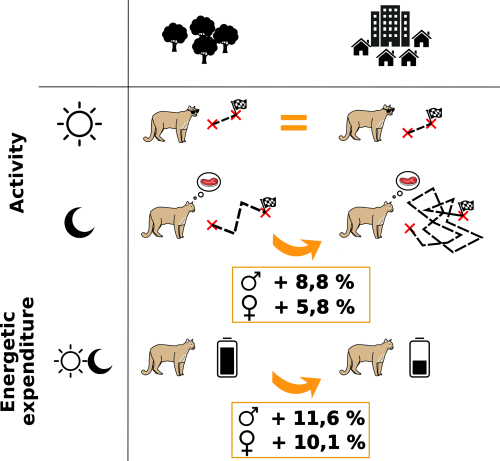

Indeed, they were right in taking into account these factors because, according to their findings, response to human activities differs between day and night and between males and females. During the day pumas are more likely to stay inactive, especially near urban areas. At night, being close to houses increases time spent active by 8.8% and 5.8%, respectively, for males and females. Consequently, estimated daily caloric expenditure increases by 11.6% for males and 10.1% for females in high housing density areas. Below you will find an outline summarizing these results:

Urban development negatively affects pumas by increasing nighttime activity and energy expenditure.Such studies underline the role of bioenergetics to estimate the costs of human-induced behavioral changes but do not provide insight on global energetic allocation. Further work is needed to understand the consequences of energetic balance disturbances and identify which individual functions are affected (growth, maintenance, maturation or reproduction). Besides, human impact could be underestimated because such tracking doesn’t allow us to know if pumas get all available energy from their prey near humans; some observations reported they often have to leave their prey because they fear humans. This partial feeding would constrain pumas to hunt more prey!

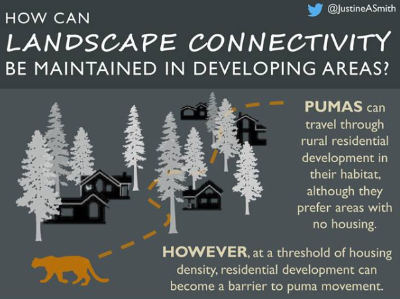

Unfortunately, this is not the only human-induced threat affecting pumas. In the region of Santa Cruz and southern California, they are targeted by ranchers, resulting in political tension about their conservation. In fact, cougars have been protected since 1990. However, 98 pumas are killed each year due to depredation hunting permits. It appears necessary to ensure coexistence between urban development, human activities, puma populations and their prey. In a recent study, development strategies are suggested, such as rural residence development, to ensure landscape connectivity and conservation of parcels where pumas have been geo-located. Nowadays, no cities are expanding regarding puma, deer or other wild animals’ living areas (to our modest knowledge!). The only measures taken when pumas are too close to urban zones consist in doing nothing or frightening or relocating it, and in the worst case killing it. And if designing our lives and activities regarding nature and wildlife was the challenge of tomorrow, would you be ready?

Ideal residential development maintaining pumas landscape connectivity. Graphical abstract of the paper of Smith and al 2019

This post is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.Are pesticides more dangerous when you are hungry?by Angèle Lorient

Published by the January 6, 2020 on 1:52 PM

Today, the impact of pesticides on our environment is a central issue in many publications and a major concern for all citizens. Between 2014 and 2016 the use of pesticides increased by 12%. Indeed, intensive farming currently used implies that we find in our food, in the air but also in water, traces of pesticides. A 2013 Inserm report highlights a link between exposure to pesticides and the appearance of cancer or pathology such as Parkinson's disease but also developmental problems on children. Therefore, they harm the health of humans but also the entire terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems.

Water Flea Daphnia Magna. www.aquaportail.comIn addition to using a large amount of chemicals, modern farming methods make soils less permeable. As a result, precipitation runoff is a major contributor to pesticide pollution from our streams. In order to study the toxicity of pesticides in the aquatic environment, the majority of laboratories use Daphnia as an indicator of water quality, and in particular the species Daphnia magna for their sensitivity to toxins.

Daphnies are small crustaceans measuring about 1 to 4 millimeters. They live mainly in fresh water (river, pond, lakes). They are filter feeders that help maintain the clarity of the water thanks to their ability to eat green algae. During a day they move between the bottom and the surface of the water depending on the light (photoperiod).

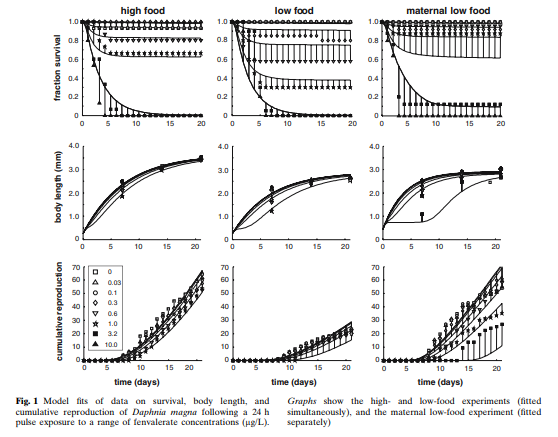

In 2006 a study was conducted by 4 scientists (2) to study the physiological responses (sensitivity, growth, reproduction) of daphnies to different dietary concentrations of the same pesticide to which they and their mothers were subjected. (high food or low food).

The study shows that lack of food does not play a direct role in the sensitivity of daphnies to the pesticide in question. However, it is one of the factors determining the level of absorption and elimination of this toxic substance by the body. In addition, the energy used to fight this toxin has a negative effect on the maintenance of vital functions.

In a period of low availability of food resources, invertebrates will have a more limited growth and a lower reproductive rate in proportion to the level of pesticide present in their environment. While the impact is less when they are subject to sufficient food resources (Fig 1).

For the different types of food resource, the effect of the pesticide concentration is proportional to the survival rate. On the other hand, we can notice that there is a threshold effect concerning growth and reproduction.

However, they also highlighted that these individuals, when no longer subject to the pesticide, found a normal activity (resilience).

This study makes it possible to highlight the potential impacts on the results of the experiments if certain non-standardized conditions vary between laboratories (concentration of food, respect of the photoperiod). As well as the differences in test organism responses between conventional environmental conditions (controlled artificial environment) and the natural environment (subject to variations).

The analysis of the results of this study raises the following questions:

- What is happening in the longer term?

- Does the repeated presence of pesticide pulses have the same physiological effects on an individual throughout his life?

- Is the speed of resilience due to the species or can it vary individually?

- Is there resiliency of newborns from underfed mothers?

It also shows the urgency of taking into account the impacts of pesticides, both on our current health, on the heritage that we will transmit, but also on our ability to reproduce. Despite the mobilization of the Ministry of Agriculture including the program "Ambition bio 2017" there is urgency. Pesticides are one of the main causes of pollution in our waterways. This pollution endangers aquatic life, as has been demonstrated, but also the drinking water resource. Should not our entire consumption system be called into question in order to be able to realistically implement the planned management plans?

This post is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.