Why should we think about cougars when planning our cities?by Amaïa Lamarins and Gautier Magné

Published by the February 3, 2020 on 2:02 PM

A puma family above the nighttime lights of San Jose - National Geographic - (photo courtesy of Chris Fust)

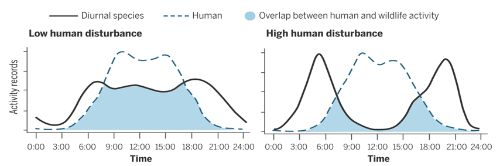

Humans have modified 75% of earth land surface which has important consequences on wildlife. In fact, human presence and activities are perceived as a threat by animals which adapt their behaviors to avoid it. Gaynor and his collaborators’ meta-analysis showed that many species are modifying their daily activities and identified 117 diurnal mammals becoming more and more active at night. Consequently, these animals face constrained access to resources and are susceptible to shifting their diet to nocturnal prey. Thus, anthropic activities influence growth, breeding, survival and community interactions of wild animals.

Shift in rhythmic activity of diurnal species due to human disturbance - Ana Benítez-López.

In southern California, the habitat of cougars, an apex nocturnal predator, is reduced by the expansion of cities. No, we’re not talking about the rampant nightclub predators (whose habitats remain undisturbed), we’re talking about mountain lions! You’ve probably already heard about pumas roaming across big cities like Santa Cruz, California. They likely are not curious tourists hoping to take in the sites, but are rather disturbed by human activities, which cause their nighttime activity to be higher in developed areas than in natural ones. This shift increases their daily energy expenditure: because of humans, pumas need to eat around 160-190 kg of additional meat per year (for females and males, respectively)! Are there sufficient deer populations to meet these needs? Unfortunately, it seems not, since a significant number of puma attacks on cattle have been recorded.

These results, showing human-induced behavioral change for pumas, come from a recent study published by members of the Santa Cruz puma project. By wide-scale monitoring of 22 wild pumas, they were able to link their behavior with their subsequent energetic expenditures: pumas’ behavior and movement were measured through spatial GPS location data, recorded every 15min, and energetic cost of movement was estimated considering their weight and travel velocity. An interesting methodological point to note: in order to avoid underestimating the energy expenditures via GPS tracking, scientists calibrated their estimations using accelerometers. Thanks to these methods they figured out the effect of housing densities on pumas’ activity and energetic costs, taking into consideration the time of day and sex of the animal.

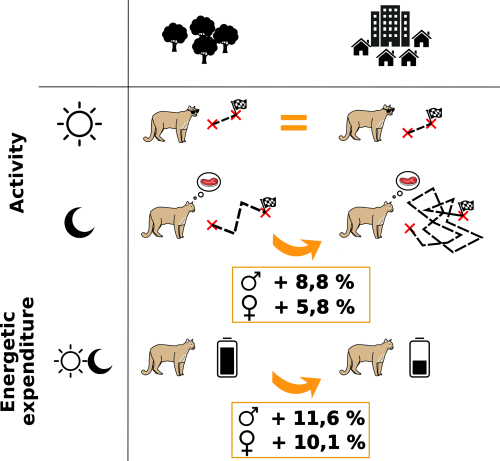

Indeed, they were right in taking into account these factors because, according to their findings, response to human activities differs between day and night and between males and females. During the day pumas are more likely to stay inactive, especially near urban areas. At night, being close to houses increases time spent active by 8.8% and 5.8%, respectively, for males and females. Consequently, estimated daily caloric expenditure increases by 11.6% for males and 10.1% for females in high housing density areas. Below you will find an outline summarizing these results:

Urban development negatively affects pumas by increasing nighttime activity and energy expenditure.

Such studies underline the role of bioenergetics to estimate the costs of human-induced behavioral changes but do not provide insight on global energetic allocation. Further work is needed to understand the consequences of energetic balance disturbances and identify which individual functions are affected (growth, maintenance, maturation or reproduction). Besides, human impact could be underestimated because such tracking doesn’t allow us to know if pumas get all available energy from their prey near humans; some observations reported they often have to leave their prey because they fear humans. This partial feeding would constrain pumas to hunt more prey!

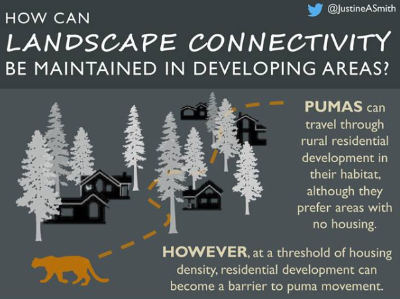

Unfortunately, this is not the only human-induced threat affecting pumas. In the region of Santa Cruz and southern California, they are targeted by ranchers, resulting in political tension about their conservation. In fact, cougars have been protected since 1990. However, 98 pumas are killed each year due to depredation hunting permits. It appears necessary to ensure coexistence between urban development, human activities, puma populations and their prey. In a recent study, development strategies are suggested, such as rural residence development, to ensure landscape connectivity and conservation of parcels where pumas have been geo-located. Nowadays, no cities are expanding regarding puma, deer or other wild animals’ living areas (to our modest knowledge!). The only measures taken when pumas are too close to urban zones consist in doing nothing or frightening or relocating it, and in the worst case killing it. And if designing our lives and activities regarding nature and wildlife was the challenge of tomorrow, would you be ready?

Ideal residential development maintaining pumas landscape connectivity. Graphical abstract of the paper of Smith and al 2019

This post is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.